About two weeks ago I wrote about a ‘post-exam’ lesson I had given to a student who had sat her Grade 5 exam only a few days earlier. In her 40 minute lesson we worked through six new pieces that she was to start working on, ranging from a ‘hard’ Grade 3 piece through to middle-of-the-road Grade 5 standard pieces. The next scheduled lesson was abandoned due to a sporting injury (a not uncommon occurrence amongst piano students who also maintain a sporting program alongside their instrumental studies!), so the two-week break between lessons really only allowed the student about 7 or 8 days to get any practice done. But even so, she returned having spent about 6 hours in practice since her last lesson. The Diversion 4 by Richard Rodney Bennett was fluid and basically flawless, but a little too slow. This week my student is focussing on creating balance within the right hand part, which consists of both

Piano Teaching

Some of the things that have been on my mind

In contrast to my normal 1000 word blog entries, today’s is one of my “quick – make a list of all things I want to blog about” pieces. Last week (for the first time) I joined in a twitter conversation held every Tuesday at 11am Australian Eastern Daylight Savings Time called #musedchat. It’s an hour of thought-exchange between music educators, most of whom are working in classroom contexts, most of those it seems working with high school aged students. Last week’s topic looked at ways of assessing musical understanding, and I loved each of the 60 minutes spent involved in that conversation. Most music assessment looks at a student’s ability to do something, usually performing a technical feat, or recognising a musical occurrence, being able to label something appropriately, and so forth – many things which are not necessarily measuring a student’s understanding. Which raises the question, how much music education is directed to increasing or deepening understanding? I spent

What Are Piano Lessons For?

This is a very personal manifesto about the purpose of piano lessons. You may not agree. You may disagree vehemently.

Teacher As Guide: A Case Study

I’ve been writing and speaking about the responsibility of the piano teacher to be a guide for the student in terms of each specific new piece of repertoire, the importance for piano teachers to take this role seriously. Students gain enormous value from good guidance both in terms of enjoyment and sense of accomplishment as well as saving the student a lot of wasted practice time. This last week a student of mine had a ‘post-exam lesson’ – that first lesson after the exam where new repertoire is assigned, and the piano teacher spends more time playing the piano than the student does. Even though my student had just passed Grade 5 Trinity Guildhall (with distinction, as it turned out) her first new assignment was Diversion 4 by Richard Rodney Bennett (a piece considerably easier than Grade 5!). Before she played it through I talked about the style of the piece: it’s clearly a 20th century work, but very lyrical,

Examination Rules: How Many Hours Practice Does it Take?!

One of my ‘rules’ for a while now has been that students need to do at least 100 hours practice

read more Examination Rules: How Many Hours Practice Does it Take?!

Leaving ‘Laminating’ Behind: Step 1 – The Skill Set

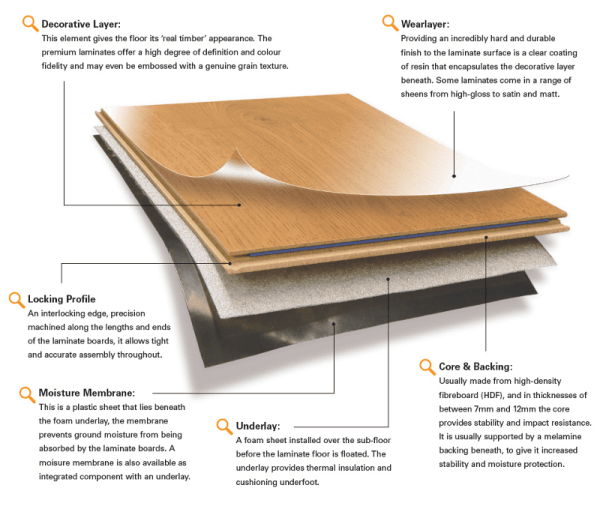

I’ve said it before, we piano teachers teach the way we were taught. And we do it because deep in our musical bones and our pianistic DNA we truly believe we were taught well. But upon deciding that, while our teachers served us well, we can serve our students better, how do we turn around a lifetime of habits we now perceive to be downright dangerous? The downright dangerous teaching habits are what I’ve called The Lamination Technique, where students are asked to learn the notes first, the rhythm next, then put hands together, then articulation, then dynamics, and so on over a period of months until finally the phrases are all welded together into something called a ‘performance’. The first thing is to truly believe that there is a better way, even if you are not quite sure what it might be. Like they say, if you don’t want anything to change keep doing what you’ve always done! If

read more Leaving ‘Laminating’ Behind: Step 1 – The Skill Set

What does it mean to ‘learn’ a piece of music?

I’m asking this question in response to some conversation following on from my Repertoire Rules (for students) post, where the

How (not) to Learn a Piece of Music

It seems that once upon a time in the not so distant past a general consensus amongst piano teachers existed

Repertoire Rules (for students)

These rules are rules about students and repertoire, but really these are more rules for piano teachers… So for any students reading this post – this is the stuff your teacher should know! In the 11 month history of my blog I’ve discussed how students having access to more books of music is going to have a positive impact on their musical literacy, and how learning a large number of pieces each year will have commensurate educational benefits. I’m not going to rehash either of these posts, but rather cut straight to: what are the rules we need to apply to students and their repertoire? First up: a rule of thumb. If your student learns less than 26 pieces per annum they will be bored. They may not tell you they are bored, but they are. If learning 6 pieces a year truly engages their curiosity they must be almost entirely disinterested in learning to play the piano. On the other

Repertoire Rules (for teachers)

Yesterday I gave a one hour presentation at the BlitzBooks-organised Winter Piano School held in Sydney’s CBD with the title “An In-Depth Look at Repertoire Collections”. I went along with a suitcase full of books for an intensive show and tell session: collections for beginners, graded collections, period-collections (Baroque, for instance), geographical collections (Australian, for instance) and stylistic collections (tangos, for instance). 16 kilograms of print music material. My intention was to begin with a short spiel about the importance of repertoire, covering the need for teachers to invest their time and money in getting to know new pieces every year, as well as the need for students to work on a much greater number of pieces than traditionally has been the case (a topic I’ve covered in my blog previously). And then I was going to launch into the music in the suitcase… The “rationale for repertoire” part of my presentation was supposed to be about how music is